Why Air Canada Wants More Range in its Long-Haul Fleet

Air Canada's chief commercial officer geeked out with me over whether the airline will choose Airbus or Boeing for its next widebody. Also, he shares a small disappointment with the A321XLR.

Dear readers,

When Air Canada ordered 18 Boeing 787-10s in 2023, Boeing said the first tranche of aircraft would arrive within about two years, which would allow the airline to capitalize on the post-covid boom for long-haul travel and cargo. However, Air Canada has received none of those airplanes yet, and while widebody profits remain robust, the airline recently decided to drop four jets from the order. With deliveries running behind schedule, the airplanes at the tail end of the order simply will arrive too late.

“We wanted those aircraft in ‘25,” Mark Galardo, Air Canada’s chief commercial officer, told me in an interview last week. “We wanted those aircraft, big time, in ‘26. But our first aircraft will probably arrive somewhere between June and July of ‘26, and we are probably looking at three or four months to get the aircraft certified in Canada. It has become a Q4 ‘26 event. It is basically two lost summers’ worth of value to us. So as that moves more and more to the right, it begs the question: where are we actually going with this widebody fleet long-term?”

Galardo now is thinking deeply about the long term, and Air Canada’s next (and bigger) order. More specifically, Galardo told me he is looking for an airplane to satisfy Air Canada’s global ambitions in the 2030s, as it replaces many of its older A330-300s, its Boeing 777-200LRs, and (depending on the timing of deliveries) its Boeing 777-300ERs. He’s preparing for a full bake-off between Airbus and Boeing.

For the 2030s, Galardo told me his priority is even more range. If aircraft size and fleet commonality were the only considerations, Air Canada likely would order more 787s to join a fleet that already has 40 of them. But in the next decade, Air Canada is orienting its fleet and network around Canadian immigration trends, and the top three countries of citizenship for new Canadian permanent residents in the first half of 2025 were India (by a large margin), the Philippines, and China.

To profitably fly customers and cargo on those flights — and boost margins on existing winners like Australia — Galardo said he needs a plane that reliably can fly very far, or around Russian airspace (if needed). “Brian, I salivate over any aircraft that’s got ultra-long-haul capability,” Galardo said.

None of this is an indictment of the 787-10. Air Canada ordered the newly updated 787-10 IGW (the “increased gross weight” Dreamliner), and Galardo said the airplane looks to be just as effective as Boeing promised. He said it can fly about 500-600 miles farther than the standard version which makes it an appropriate choice not only for major European destinations like London, but also for Hong Kong. It is also an impressive freight hauler (“one of the better cargo aircraft that I’ve studied,” he said).

Still, Air Canada decided that 14, not 18, would be enough. As for whether Boeing owes Air Canada for these delays, Galardo said only: “We have an agreement with Boeing, and we’re executing our rights within that agreement and have come to an amicable solution.”

OK, what’s the plane going to be?

Galardo said he has narrowed the choice to two main contenders: the A350-1000 and the Boeing 777-8X. Both likely will be off-the-shelf versions, and not the specially configured airplanes that Qantas plans to run on Project Sunrise. The A350 is a proven airplane, but Galardo said he’s optimistic about Boeing’s forthcoming entry. “Based on our interactions with Boeing, that’s a really capable airplane,” he said. “But the question is, when will that aircraft actually come to market?”

While the 787-9 IGW could be an option, Galardo said it probably can’t fly as far as Air Canada would like with a full payload. Typically, Air Canada prefers more dense configurations than competitors to account for Canada’s more limited premium demand, and more seats can limit an aircraft’s range. On many widebodies, Air Canada installs 30-40 more seats than United does on the same airplane — a big reason why Air Canada struggles to reach certain markets.

“The rule of thumb is at 16 or 16.5 hours, you’re starting to push the limit of a 787-9 at our LOPA1,” he said.

And that’s just with passengers. Galardo is also president of Air Canada Cargo, and he said the company likes to use freighters to haul goods from Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru, and then transfer items to passenger jets headed to Asia. He wants an airplane that can carry people and freight.

“When you’re flying to the Pacific, cargo is a real make-or-break between decent profitability and sustainable profitability,” Galardo said. “If those cargo bellies coming out of Asia are not full, you’re talking low-margin operations.”

Are they sure they want to make such a large investment?

I love when airlines push boundaries as they carry their nation’s flags across borders, but I (and others) wonder how pragmatic this is: how many of these ultra-long-haul operations actually make money, considering the cost of the airplanes with this range?

Galardo said Air Canada can make money with 15 hour-plus stage lengths — even now, when it often flies the wrong aircraft for the mission. He points to Sydney as an example.

“The margins are very interesting,” Galardo said. “The only aircraft in our fleet that’s capable of flying there with a decent payload, both cargo and passenger, is the 777-200LR. That’s not a sustainable aircraft in the long term.”

In other cases — like a trio of new routes from Vancouver (to Singapore, Bangkok, and Manila) — Air Canada is stretching the 787-9. With a new airplane, Galardo said those routes could be more successful than they are currently, because all three markets have significant cargo potential that Air Canada can’t capture with the 787-9. There also are other routes that Air Canada doesn’t fly today but could in the future. “We’d like to eventually look at South Africa,” Galardo said. “It just requires operational capability.”

Then there’s routes caught up in Russian overflight restrictions. “Over time, we’re going to crawl back into China,” he said. In June, Air Canada launches its flights from Eastern Canada to mainland China since the pandemic: Toronto-to-Shanghai, a route that returned after the operations and planning teams found a way to do it while avoiding Russia. “We’re really testing the limits of that airplane,” Galardo said.

But the biggie is India. Galardo called Canada-to-India a “massive market,” telling me it has doubled in size during the past decade. In the winter, more people travel between Canada and India than to the United Kingdom, France, or Germany, he said, and yet Air Canada currently offers a small nonstop schedule that will become even smaller next year when it drops Montreal-to-Delhi.

“With Russia overflight constraints, we need an aircraft that’s capable of attacking that market, without a passenger penalty and without a cargo penalty,” he said.

Some of you might be wondering why Galardo is so sure that this Russia issue will persist — or even more broadly, why he’s so sure that the demand-supply equilibrium will continue to favor North American airlines that fly ultra-long-haul sectors.2

Galardo, of course, can’t be sure about any of this stuff, but he told me that both the A350-1000 and Boeing 777-8X are versatile enough to fly many routes at compelling economics. One thing he likes is the vast space both airplanes have between doors 1 and 2. In both airplanes, he said, Air Canada can install at least 40 business class seats. (The 787-10 has the same feature, one reason Galardo likes it so much.)

“The real estate between door 1 and door 2 is the most valuable real estate in the industry,” Galardo said.

I wasn’t sure why that matters so much, considering so many airlines split business class cabins between two zones. But Galardo, a lover of efficient LOPAs, called himself a “purist,” telling me that monuments and cabin dividers eat up a lot of space without producing revenue. “The details show up in the margins,” he said.

So even if the A350 or the 777X never flies 18 hours, Galardo said it still will be a revenue winner while offering the most flexibility, “whether we fly over Russia or fly around Russia.”

Would creative thinking solve any of these range problems?

If it is not already clear, I really like Galardo, who started at Air Canada as a summer intern in 2004 and has held a range of revenue and network roles since then. He is an ultimate aviation geek, a term I use with endearment.

I also use that term to describe United’s Patrick Quayle, who specializes in creative (and very av-geeky) solutions to problems. Quayle is broadening United’s breadth in Asia by using Tokyo and Hong Kong as transit points to cut down on the need for so many ultra-long-haul flights that suck up aircraft time. I asked Galardo if he’s channeling his inner network planner, like Quayle. “We’re always looking at unique opportunities,” Galardo said. ”I know it sounds like a talking point, but I’m telling you straight up.”

Air Canada also has historic traffic rights, though likely not as many as United. Galardo told me that the airline can fly from the UK and Switzerland to India, and from Japan to Thailand, and from Argentina to Chile and Brazil. It has used some of those rights over the years and now flies São Paulo-to-Buenos Aires and London-to-Mumbai. Of the India route (which re-started after Russian airspace closed), Galardo said: “It actually is somewhat profitable. I won’t profess that it’s the highest margin thing we fly.”

But for Air Canada, these are niche opportunities. He commended United for its Tokyo and Hong Kong expansion but said Air Canada (which is not in a transpacific joint venture with United and ANA) looked at launching Bangkok from Tokyo and decided it didn’t have enough feed and slots in Tokyo to make it work.

I also was curious about Boeing 777-200LRs. I don’t think I’ve ever heard an executive say anything good about the airplane, but I also know that airplanes without suitors can be purchased very cheaply. Galardo told me that they looked at adding some 777-200LRs, but reconfiguring cabins would cost $30-40 million (U.S.) per aircraft.

“And then on top of that, you’ve got pretty significant fuel burn penalties,” he said. “You’ve got like 3-5 years left on flying that aircraft. You can’t get a suitable IRR from that investment.”

On the bright side, Air Canada made the right fleet decision for the time, considering it briefly operated a small fleet of A340-500s. At least the 777-200LRs are still flying.

“They work OK on Sydney because of the high yield, and they’re OK on Delhi,” Galardo said. “Then we have another two that shift around into transatlantic operations, just for rotation purposes. And obviously we carry a big penalty there.”

Speaking of range, how far can the A321XLR fly?

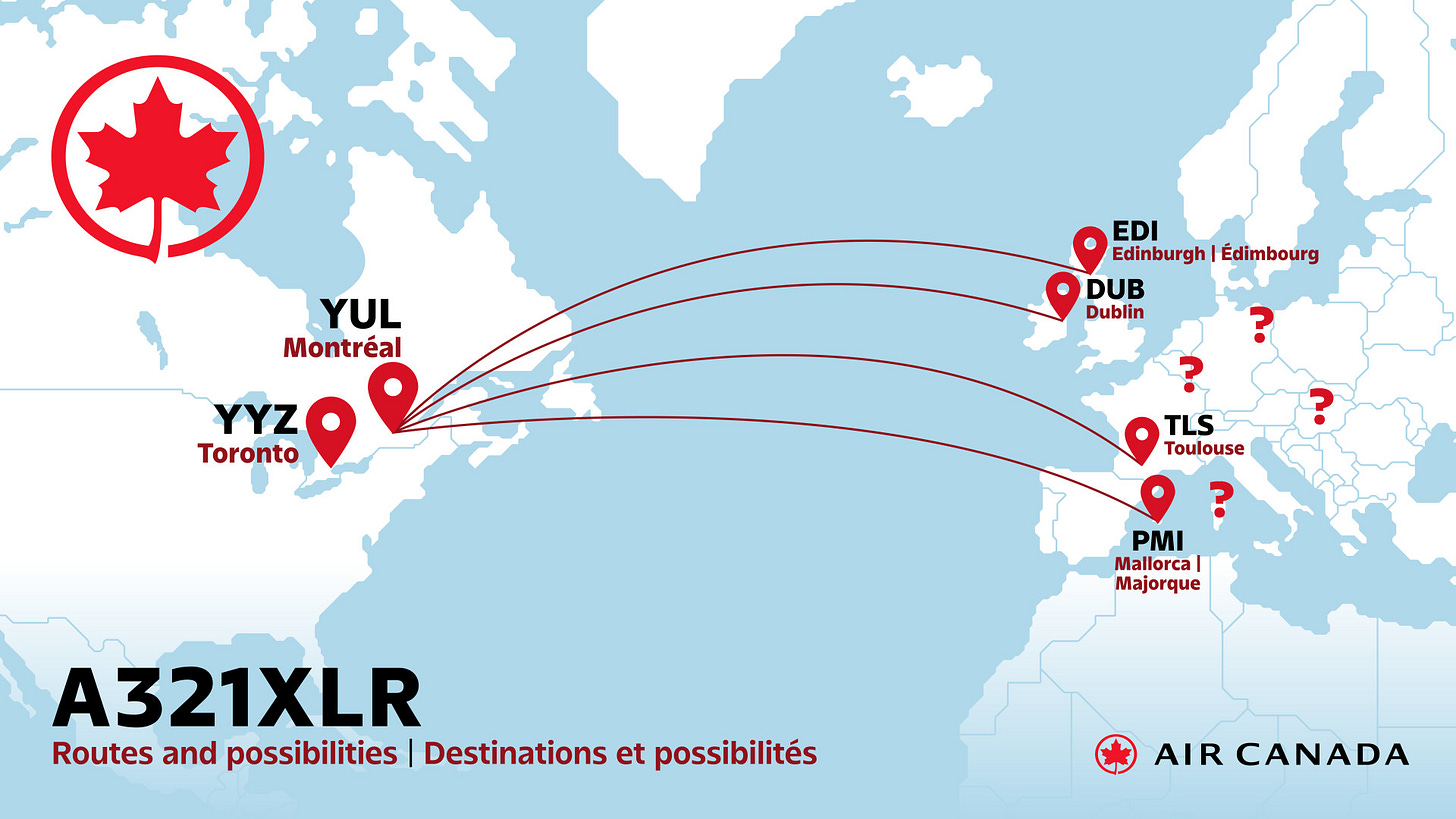

I have heard other airline executives knock the A321XLR, saying it may not open as many new routes as airlines had hoped because it doesn’t have as much range as Airbus promised. Galardo expects to get his first airplane in the first quarter of 2026, and he said he believes range is not an issue. “It’s exactly as advertised,” he said.

But he does have concerns. The problem: Airlines had hoped to fly to smaller airports that historically don’t have long-haul service, but they’re finding that some of those airports also can’t accommodate the XLR.

“If you’re in a smaller airport where you have an obstacle at the end of the runway, or you have a short runway, or you have heat concerns, it starts to cut down the payload,” Galardo said. “That’s a concern, and that’s something I don’t think we factored in when we made the purchase decision.”

That means some long routes (like Toronto-to-Prague and Toronto-to-Budapest) will work fine in the summer. So will other thin routes that Air Canada plans, such as Halifax-to-London and Montreal-to-Edinburgh. The XLR will replace 737 Max 8s on both sectors.

But given the big demand for Southern Europe, Air Canada has been looking at expanding into Spain — Bilbao, Seville, and Ibiza, to be specific — and the XLR may not work for any of those routes.

“Those are things that are a little bit disappointing,” Galardo said. “But for mainstream Europe or secondary European markets with long runways, the aircraft performs just fine.”

Most of mainstream Europe, that is; Galardo said the operations team is concerned about Madrid because it’s so hot in the summer. “If you’re leaving at 12 noon out of Madrid, you’re talking 37-38 degrees Celsius,” he said. “It’s punitive.”3

He cautioned that this is not a complaint and that Air Canada never expected the 787 would be a true ultra-long-haul airplane. “The 787 has lived up to everything Boeing has promised us,” he said. The airline has eight 787-8s and 32 787-9s.

As you know, North American airlines have benefited as Chinese airlines retreated from Canada and the United States. When they were growing so much before covid, and selling cheap one-stop fares, they pushed down yields for all airlines.

A few days after this interview, Iberia announced it will fly Madrid-to-Toronto five times per week on the XLR starting in June, with roughly the same cabin configuration as Air Canada. In our discussion, Galardo and I spoke about how different airlines have different tolerances for aircraft performance. But in a message after Iberia’s announcement, Galardo told me that Air Canada might revisit some of its concerns about Madrid.